Somewhere in the Pacific Northwest, on the far side of Elphame’s boundary, not long after the end of The Summer Queen . . .

The knock on the door didn’t wake her up. She heard it as if from a great distance and briefly stirred, but then sleep pulled her under again.

The shrieks that ensued when the maids let themselves in were harder to ignore.

She sat bolt upright, not remembering, at first, where she was. The chill made her clutch the blankets closer; they were velvety and thick, and would have been too warm anywhere else. Over the solid wall of black fur in the bed beside her, she made eye contact with the human girl in the doorway, who had stifled her screams with a trembling hand clamped over her mouth. There was another maid just behind her, peeking over her shoulder with wide eyes.

The hound lifted its head, studied the two women by the open door for a long moment, and then lowered its snout back onto its paws. The maid who had come in first looked ready to faint dead away.

“Um, it’s all right,” Hazel said hesitantly. “This is Lupa. It won’t hurt you.”

She patted the top of Lupa’s massive head, to show them it was okay.

“Pardon, miss,” the maid in front said in a high, fearful whisper. “We—We came to help you dress for breakfast.”

Hazel shrank a little lower under the covers. The thought of strangers helping her get dressed made her stomach shrivel with horror. Beside her, Lupa growled, its eyes swiveling toward the maids, though it didn’t otherwise move.

“Could you just, um, show me what I should wear? And then I can put it on myself? Please?” Hazel asked, in a small voice.

The maid glanced at Lupa, and then at her companion behind her, and then nodded rapidly. She took a few steps forward, but stopped when one of Lupa’s ears pricked in her direction. Hazel sighed.

“Lupa,” she whispered, leaning in close. “Can you hide until they leave?”

Lupa blinked at her but obliged. It stood up and stretched ostentatiously, its large tail beating against the mattress and its claws digging into the sheets. She lifted the edge of the blanket, coaxing Lupa into the little dark cave beneath, and Lupa nosed its way in, disappearing, which was a little like watching a Great Dane squeeze itself gracefully into a handbag. There wasn’t even a lump in the blankets to show where it had vanished.

“Where did it go?” the maid asked worriedly, looking around as if expecting Lupa to pop up behind her like an evil jack-in-the-box.

“Nowhere. It’s gone,” Hazel said, and coughed to cover the growl emanating from under her bed.

This was the first—but far from last—poor impression she would make upon the residents of the Winter Court.

It had been a tiring journey of several days; only last night had they finally arrived and met with the Winter Queen. In the end, Queen Ceresia had let them stay, but Beor was quarantined in the infirmary, where no one would catch the jade rot from him. While Queen Ceresia gathered her allies and deliberated with them over what to do about the rot, Hazel was required to act as the Summer Court’s representative. She was still the daughter of the late Summer King, still a Princess of the Seasons. For now. Though the Summer Court had all but dissolved, Hazel’s royal status wouldn’t change unless another one took its place as Winter’s counterpart in the high court of Elphame. So she would obey the queen’s every word and let the Gallowglass escort her everywhere until she learned her way around the Winter Court’s serpentine stone corridors.

She felt very alone. In the Summer Court, Ephira had been there to make introductions and fill Hazel’s uncertain silences. She had never run out of things to say. Without her, Hazel didn’t know how to even begin talking to anyone. She ignored the curious glances she attracted as she scurried along at Queen Ceresia’s heels, willed away the mortified flush that rose to her cheeks when she mispronounced the name of the ambassador from the Court of Masks, and tried not to shiver too obviously at mealtimes. Nothing got past the queen, though. She said it was unacceptable that a fairy—let alone a fairy of the Summer Court and daughter of the esteemed Lady Thula—should be unable to perform a simple warming enchantment. On the second day after Hazel’s arrival, her lessons began. The children of the Winter Court took their lessons together, though they were all different ages and practicing at different levels. Hazel was grouped with the littlest ones, and was painfully aware of how ridiculous she must have looked, learning baby spells surrounded by toddlers and still barely keeping up.

She avoided looking at the group of students her age; if they thought she was antisocial, that was still better than letting them see how self-conscious she felt. But one of the boys approached her after the lesson.

“Excuse me, Princess,” he said, before she could flee. Reluctantly, she turned to him. His wings were bright green and leaf-shaped, like a katydid’s, but his skin was milky white, almost translucent, so that she could see the faint purplish tracks of his veins underneath.

“Hello,” she said warily.

He smiled, revealing sharp incisors. “I have a riddle for you.”

“Okay,” she said. Then she wanted to kick herself. Ephira would have turned up her nose and said, I didn’t ask for a riddle. Hazel, did you hear me ask for a riddle? No? The poor dear is confused. Dazzled by my beauty, perhaps?

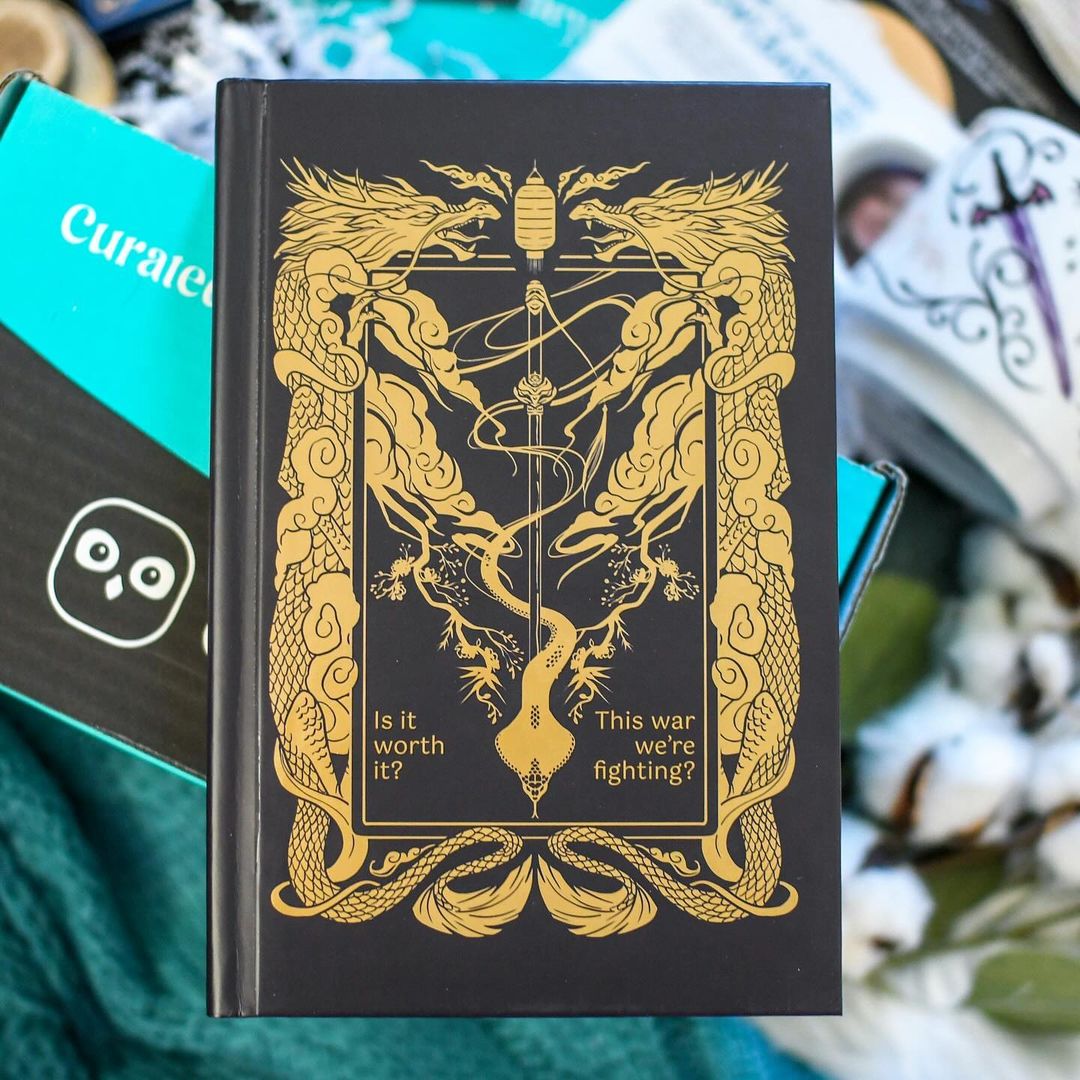

But Hazel couldn’t backpedal now. The boy said, “I am not glass, though brittle I may be. Like a hare among foxes, I hope they do not see. As crude as my manner is my mimicry. What am I?”

His friends loitered a short ways off, close enough to overhear. She could see them smirking over his shoulder; one of them hid a giggle behind her hand. The boy waited for her response, his smile fixed in place.

“A gifted poet,” Hazel answered tonelessly, channeling Ephira to the best of her ability and refusing to take the bait. “Thank you for the riddle. I will have to pay you back another time.”

She left without giving him a chance to reply, head held high, though she knew that if that had been some sort of test, she had failed.

She asked the Gallowglass to show her a quiet place where she could practice the enchantment they had worked on, and where—she didn’t say this part—no one would be around to see her mess up. They led her to a garden within a kind of indoor courtyard, light shining down from some high place, magnified by the crystal shards in the walls. She was trying to take away a ladybug’s spots and replace them with stripes. With no success. As the hours wore on, she could feel her frustration mounting, and that probably didn’t help. But it was the least complicated form of illusion, and one she knew she could do.

During the week she had spent with the Summer Court, she had taken lessons with a tutor that Princess Narra had assigned her. Hazel had wanted to learn the look-away charm that she’d seen the other kids use—it would be a good first step toward being able to go back to the human world, and it seemed a more attainable goal than full-fledged illusion. But the tutor had informed her that look-away charms carried an element of magical compulsion that was “far beyond” her current level of experience. So they would start with the basics of illusion-weaving.

One of her very first assignments had been to change the color of a flower petal from white to red. She had tried really hard, but all she could manage, after what felt like about a thousand attempts, was pink—not even pink, more like an ugly salmon color that reminded her of the chairs in the waiting room at the orthodontist’s office. When the tutor had wrapped up their lesson for the day, leaving Hazel with her small pile of sad, fishy flower petals, Ephira had sidled up to her.

“There’s a secret to weaving that she hasn’t told you yet,” Ephira said.

“Really? Why not?” Hazel asked.

Ephira laughed. “You don’t want to know what the secret is first?”

“That too,” Hazel said, feeling awkward.

“No, you’re right. If she was trying to sabotage you, that would be vital information.”

Hazel wasn’t so sure about that. Some of the fairies were a little cold to her because—probably a lot of reasons. Because she was a changeling, and a stranger, and maybe also because she looked so much like her mother, Lady Thula, who apparently hadn’t been very popular. But Hazel didn’t see how it would do her any good to find out if her tutor was one of them. She’d probably be happier not knowing. She couldn’t explain why she’d asked at all; it had just come out.

“Okay, then what’s the secret?” she asked Ephira.

Ephira leaned forward, her black hair falling over her shoulder, her wings slowly opening and closing behind her. She never held them still, even though most of the others usually kept theirs folded against their backs. The motion threw little rainbow fragments of sunlight like a glittering shawl over her blue skin.

“You needn’t worry. She hasn’t told you because she’s probably forgotten. At her age, small illusions are second nature. She doesn’t have to think about it.” Ephira opened her hand to reveal a bracelet made from blue crystal beads. “But never mind. Look. I made this for you.”

“You did?” Hazel asked, startled, touched, and a little amused. Ephira would gift her something almost the same exact color that she was.

“Yes,” Ephira said. “But you can only have it if you can turn one of these beads green. Just one, even for a moment, and it’s yours.”

“I don’t think I can do anything but pink yet,” Hazel said, hearing the whine in her voice but unable to stop it.

Ephira shrugged. “Do you want it or not? Is it not pretty enough for you? I happen to think it’s quite lovely.”

“No, I do want it,” Hazel hurried to assure her. She really did, too. It was pretty, and better yet, it meant they were friends, maybe. There were a lot of things she didn’t understand about fairies yet, but she was willing to bet that friendship bracelets were a universal concept.

She concentrated harder than she had on all those flower petals put together.

One of the beads turned green. And then the rest of them did, too, the color washing across them like dawn over a grassy field.

Hazel gasped, but Ephira just laughed, joyful and unsurprised. “You see?”

“How did I do that?”

“You have to want to change the object of your enchantment. Desire is the key to weaving,” Ephira said. “The best weavers can trick themselves into wanting things they don’t. Small wants are easy, though. You probably don’t care if the flowers are white or red, but you can convince yourself you do. Find a reason to wish them red. Or focus on how they can help you get the things you do want. Like more interesting lessons.”

Ephira placed the bracelet in Hazel’s hand. Hazel closed her fingers around it. When she opened them, it was blue once more.

“I like it better this way,” she said, and Ephira had smiled brightly at her.

Now, she looked down at the ladybug and sighed. She didn’t want it to have stripes. What did a ladybug even need stripes for? And she was too tired and homesick to care about advancing to more complicated lessons yet. She did want that—or she’d want it later—but right now, she mainly just wanted to go back to her room and cry into Lupa’s fur for a little bit. If enchantments were based on desire, it was no wonder she couldn’t get it right. Conflicting desires meant broken enchantments.

She had chosen this—she knew she needed to be here, that helping the Summer Court was the right thing to do, and that hadn’t changed. But that didn’t make it easy. When she had first gone to the Summer Court, it had been to protect her family, and the fear and adrenaline that had spurred her to make that choice had eclipsed all other emotion. And Leo had come right after her—as part of her, deep down, had hoped he would. Then her week in the Summer Court had felt kind of like sleepaway camp, a temporary thing, even when she had considered the possibility that she might need to stay. Might want to stay. She had known the whole time that she’d see Leo again after a few days. It had never felt like a real separation. She had underestimated how much harder it would be to leave home now that she was truly alone.

She blew gently at the ladybug, encouraging it to fly away.

“Go on, get out of here,” she said. “I’ll tell them I squished you by accident. You better not let them see you.”

An amused voice behind her said, “Now, my dear, you might be capable of lying, but that certainly doesn’t make you a talented enough liar to fool the likes of Queen Ceresia.”

Guilty, and a little nervous, Hazel turned. The speaker was a man who looked to be in his mid-twenties—which meant he could’ve been anywhere from twenty years to several centuries old. She had seen him only in passing, but he was memorable even for a fairy, with waves of wild dark hair that fell down his back, the ends floating up into loose curls, dark brown skin, and eyes the color of reflected sunlight, pale and gold and a little hard to look at. He wore a crown of woven willow, glittering with drops of topaz. It was the Autumn Prince.

The Autumn Court was one of Queen Ceresia’s most faithful allies, and the first she’d summoned upon Hazel and Beor’s arrival. Hazel wondered if she should bow or if, as a Princess of the Seasons, she technically outranked him, and whether it would be worse to bow when she shouldn’t or to not bow when she should, and then she wished Ephira were here to nudge her in the right direction, and then she realized it was too late anyway because he was strolling across the garden to join her.

“I wasn’t really going to lie,” Hazel said, and felt her face go hot with embarrassment at how defensive it sounded.

“I don’t doubt it,” he said. He held out an elegant hand, and the ladybug landed right on the tip of his finger. “But what has this poor creature done to you, to deserve such cold treatment?”

“I was letting it go.”

“But where? It is trapped. It will never see the sun again.”

Despite the ominous words, his smile was brilliant and kind.

“Can’t it get out the same way it got in?” Hazel asked hesitantly.

At the end of their journey, as they reached the mountain range where Beor was certain the entrances to the Winter Court lay hidden, Beor had sent her and Lupa on alone. Beor was known to the Winter Court as a loyal subject of King Illanthus, and even though the king was gone, Beor felt it unlikely that any of Queen Ceresia’s sentries would reveal themselves to him. But they would find Hazel, he promised, and it wasn’t long before one of them did—a gargoyle that scared her half to death when he stepped into her path, his unforgiving stone face looking down at her from a considerable height. She had begged to be allowed to speak with the queen; and then, as the gargoyle had started to lead her into the caves, she’d had to insist on going back for Beor first.

The gargoyle had not been happy about it, and she had been afraid he’d just leave, and then she’d never find a way inside, and she and Beor would’ve come all this way for nothing. But he had finally agreed to lead the both of them through the caves that sloped gently downward and into the bowels of the Winter Court. There were many entrances, Beor had explained in a gruff undertone as they’d followed the sentry. But they were carefully concealed; the one the gargoyle had come out of was a narrow crevice behind a jutting stone slab that she would never have spotted even if she’d known exactly where to look. The path had been winding, forking off in other directions countless times, and she had given up on keeping track of the turns they took. But she could have, theoretically, if she’d been less exhausted.

“Certainly, it could go back the way it came,” the Autumn Prince said, “if it was both clever and lucky. The tunnels are complex. There are miles of them, all interconnected, and many of them lead to dead ends or lethal traps. The gargoyles rearrange them in the night, so that the paths are ever-shifting. Even a frequent visitor such as myself would be quite lost navigating them without a guide. Except . . .”

He trailed off. Hazel inched closer almost without realizing it.

“What?” she asked.

“I do know another way out,” he said, musingly. “It wouldn’t be of any use to me, of course—but, for a winged creature, it will suffice. Would you be so kind as to help me escort this ladybug to its next destination?”

Hazel knew better than to follow strange men to unknown places, even if he did have a friendly smile. But the Gallowglass responsible for her welfare still waited for her at the entrance of the courtyard, and had made no move to stop him from approaching her. She still had Lupa in her shadow, too, ready to spring into action at the first sign that Hazel needed help. The Autumn Prince didn’t have a reason to hurt her, and would anger Queen Ceresia if he did. Probably.

And for the first time in days, Hazel wanted something other than to go home.

She nodded, and they went, the Autumn Prince walking slowly so that she wouldn’t have to match his longer strides.

“If you would indulge me,” he said, “I would like to know more about your home in the human realm. Could you tell me about it?”

“I guess,” she said, a little taken aback. The children of the Summer Court had wanted to know all about the human realm, but the grown fairies had never shown any interest in her past. She couldn’t imagine that a prince of Elphame would care to hear about geometry homework and bike rides at St. Sithney’s Park. “But why?”

“I have rarely visited, and I am curious about it. Isn’t that reason enough?”

And Hazel, following him into a softly lantern-lit side passage, leaving the garden and her inattentive guard without a backward glance, agreed that it was.