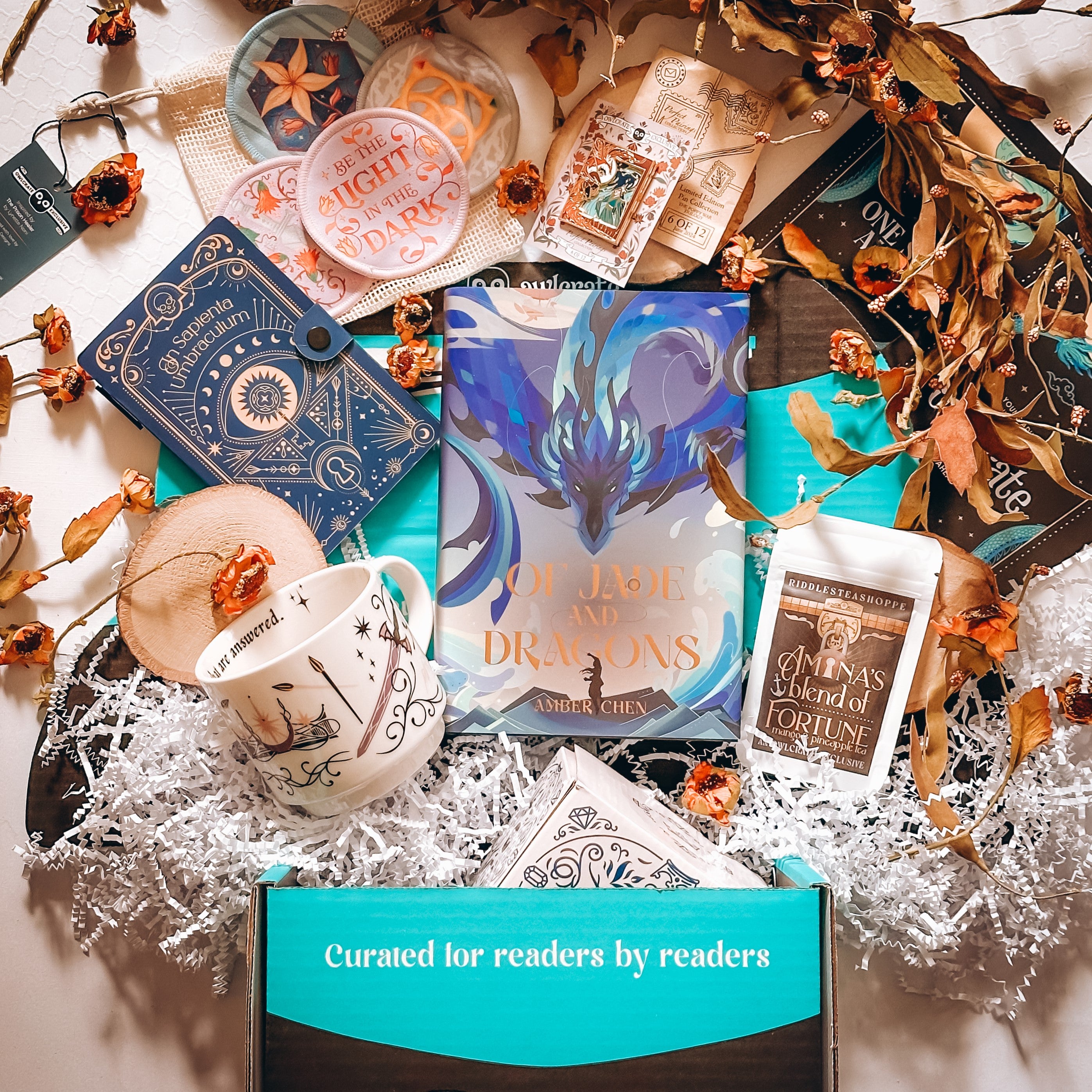

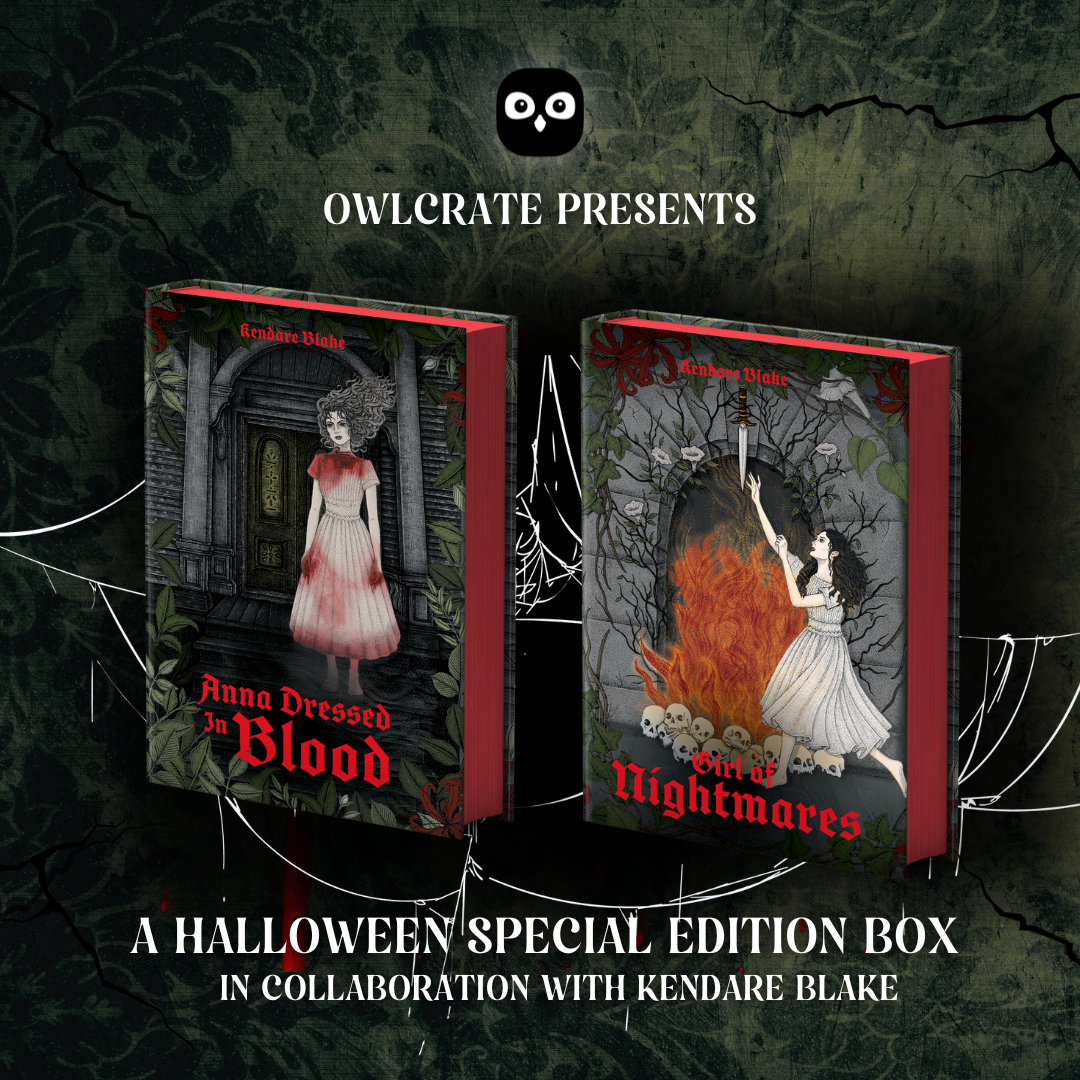

Thank you so much for ordering our January 'COURTING THE FAE' box! We hope you enjoy this exclusive bonus scene from

The Buried and The Bound by Rochelle Hassan.

Last week, three students had gone missing from Towne High, and Aziza was angry with herself because she hadn’t figured out what was doing it yet. It was probably a sandman keeping their classmates trapped in an endless sleep so that it could feed on their dreams, Aziza said, and they would need to find them before they starved to death.

—The Buried and the Bound

Towne High didn’t have a basement.

It didn’t have any abandoned wings or disused bathrooms, and it wasn’t located on top of a former cemetery. The building had never been a prison, an asylum, or a sketchy hotel. No one, to their knowledge, had ever died there. It was an unmystical concrete slab all the way down to the foundations, without so much as a haunted footstool to redeem it.

Aziza was sure the missing kids were still in there. But she and Leo had searched the whole campus by day and found no trace of them.

“We have to go at night,” Aziza said. “Sometimes, when you’re dealing with a sandman that’s gotten unusually powerful, it can . . .” She trailed off into an uncertain gesture with the hand that wasn’t in a brace, a swirl of her fingers through the air. “Change things. In the dark.”

“Like, we open a door and instead of the cafeteria there’s a shadowy portal into the sandman’s secret lair?” Leo asked, sounding intrigued in an abstract sort of way, and not like someone who was about to voluntarily walk into the aforementioned shadowy portal should it turn out to exist.

“No,” she said, dragging the syllable out. She frowned pensively. “Do you ever have the kind of dream that’s so realistic you don’t notice you’re dreaming? Even when something impossible happens. And after you wake up, for a few minutes, it’s still real to you.”

“Uh,” Leo said. “No.”

“Sometimes,” Tristan said.

“It’s like that,” she said. “You’ll see. If I’m right about this.”

Unfortunately, when it came to trouble, Aziza was usually right.

People were skipping class to sleep in the campus library or the locker rooms. They faked sick so they could nap in the nurse’s office, which only worked for one or two people at a time, and the others just got sent home where they, inexplicably, no longer felt all that tired. Some of the teachers were calling for bag checks and random drug testing. And some of them were getting caught dozing off in the staff lounge.

Tristan had learned all of this secondhand, since he didn’t attend Towne High. Aziza and Leo had told him about it in bits and pieces as they patrolled the boundary together. They were going to have to take care of that as soon as they could, they’d said, once the hag was gone.

He hadn’t said, We should get the sandman first, in case we don’t survive the hag. But he’d thought it.

Now he was glad he’d kept it to himself, because the hag really was gone and he got to pretend he’d believed in them the entire time. It had barely been three days—four, maybe? Tristan had slept at least one whole day. At some point, Leo and Hazel had gone back to school, with varying levels of reluctance. Tristan mostly spent his time applying for jobs on Leo’s laptop—because Leo happily shared everything with him: clothes, books, headphones, spare blankets, oblivious to the effect his generosity and lack of concern with boundaries had on Tristan. And sometimes Tristan would start to think about everything that had happened, and then to calm down he’d try not to think about anything at all, until he felt pleasantly numb. Then he’d blink and instead of the three or four minutes he thought had passed, it had been three or four hours and he had absolutely no memory of what the hell he’d done with them. That part was less pleasant.

Leo and Aziza were doing a better job of keeping it together and going about their normal lives, if only because they had normal lives to return to—unlike Tristan, who would have to build a new normal from scratch. But he knew they had all been united in hoping that they could put off the next crisis for a little while. A week off, even, would have been nice.

Then the fourth student had vanished. And that had reminded Aziza that the first three had been missing for about two weeks, at this point. They really would starve if they weren’t recovered soon.

“Who wants to sit this one out?” Aziza asked. “No one will judge.”

She delicately avoided singling Tristan out, but from their new bond he discerned that he was the one she was most worried about. He could hardly blame her. He, too, suspected that in his present state he would not be reliable in a fight against a teething puppy, let alone a gluttonous sandman.

“I don’t want to sit this out,” Leo said, with predictable valor.

“I don’t, either,” Tristan said, and meant it, though probably not for the same reasons as Leo did.

If there was always going to be more danger looming on the horizon, he couldn’t afford to spend another year working up the courage he needed to face it. He didn’t want to have to be backed into a corner, in a state of total desperation, before he acted.

He had killed the hag. It had been a rare and uncharacteristic moment of strength.

He just needed to know it hadn’t been a fluke.

Locked doors were nothing to him now. One of the hounds got him into the building through the shadows; from there, he opened the window in a first-floor classroom so that Aziza and Leo could climb in. They didn’t want to risk using the doors, in case they triggered an alarm. As it was, Aziza and Leo were covered up like burglars in case they got picked up by the CCTV cameras outside. Hats and hoods over their hair, bandanas tied around their faces, Aziza in one of Leo’s hoodies since it was baggy enough to hide her figure. Leo had tossed a beanie at Tristan before they’d left, insisting he wear it.

“You stick out the most,” he’d said.

“I can also literally disappear if I want to,” Tristan had replied. He didn’t look good in hats. He did not want to wear an ugly hat in front of Leo. A ridiculous thing to worry about, but then, being able to worry about ridiculous things was a luxury he intended to enjoy to the fullest.

“You can’t just disappear anymore. Not for good,” Leo had reminded him. Tristan had known that, but it hadn’t quite sunk in, and he kept forgetting. It wasn’t like before, when he had ties to nowhere. Now he had a place to come back to and a place where he intended to stay.

He had taken the hat and pulled it on, hiding his distinctive white-blond hair underneath it.

The building was two stories with four wings each. Plus the gym, library, cafeteria, and band room. They started upstairs, methodically, creeping down one hall and then the next, opening every door and shining their lights briefly inside.

“Sandmen like dark, enclosed spaces when they’re feeding,” Aziza had told them. “Inside closets. Under beds. They like to be close to where their victim sleeps—in the same room, if they can, or if not, one floor or wall away. In a cabinet in the basement directly beneath someone’s bed, or in a box in the attic above.”

The sandman had probably made an error, holing up in the school the way it had. People slept there, but only in short bursts—a nap in study hall or the back of homeroom—and the sandman would have preferred to feed slowly, over hours.

Sandman was only one term of many for an entity that appeared in mythologies all over the world. They were known as spirits, demons, deities—legendary beings with power over dreams and the realm of sleep. Like most fae, they were vulnerable to the effects of salt and silver. They had little interest in games and trickery; they tended to be thoughtful and perceptive, and understood humans better even than selkies did. Aziza might have a shot at reasoning with the sandman, unless it was completely feral or too young to have learned English.

But she wasn’t counting on being able to reason with it. They had come prepared for the likelihood that it would struggle.

A sack of used horseshoes was five dollars on the internet. They had each tucked one into the bottom of their backpacks for protection; a horseshoe would catch a sandman’s nightmares, stop it from putting any number of horrors into their minds. As for its sleeping enchantments, the only protection necessary from this tactic was a healthy dose of caffeine. They’d all downed three shots of espresso before setting foot in the building. It was harder for a sandman to put you to sleep if you weren’t already tired.

Leo and Aziza ducked into the classroom that doubled as the media center—rows of computers and television monitors, with extra storage in the back that they would have to inspect—while Tristan held the door open, watching the hallway. The vinyl tiles went white under the beam of his flashlight. His own pale reflection in the windows kept catching his eye.

He had sent the hound away after it had gotten them into the building. His control over them had always been shaky. They were connected to him through the stolen necromancy gift; this meant that Tristan had been forced on the hounds as much as they had been forced on him. It had taken months to make progress with them, and much of that progress had been undone when the hag had taken the power away from him, even though the separation had only been temporary, in the end. He didn’t trust them to back him up in a fight right now; he wasn’t sure he ever would again.

He listened to Leo and Aziza’s hushed voices inside the classroom, the soft sound of cabinet doors being tugged open and then nudged gently shut, the shuffle of their footsteps. Outside, a passing car, the wind, a skyward rumble that might turn into a thunderstorm. And . . .

His hand on the door tightened reflexively. He pointed his flashlight first one way down the hall, and then the other.

Nothing.

“Do you hear that?” he whispered, as Aziza and Leo slipped back out into the hallway.

“Hear what?” Aziza asked.

“The—the—you don’t, then. You don’t hear it.”

The music. Faint strains of it, like a radio was on somewhere behind a closed door. He caught only snatches of it, a few chords here and a lyric there. It sounded like—he cringed—one of his mother’s wedding playlists. Adele, Make You Feel My Love. Aerosmith, I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing. The Beatles, Eight Days a Week. If the sandman wanted to torment him, well, mission accomplished.

Leo put a steadying hand on his shoulder—slowly, giving Tristan a chance to move away, as he always did. It was very considerate of him and Tristan hated it. Hated the fact that he couldn’t simply say, You have blanket permission to touch me whenever and however you like.

“It’s going to try and come for you first,” Aziza warned him, once he’d described what he was hearing. “Stay close.”

“Of course it is,” he said under his breath. Maybe the sandman had sensed the wealth of nightmare material in his head and couldn’t resist. Maybe it could feel the fine, faint cracks inside where he had been broken by the hag over and over and had only just started to piece himself back together. Maybe it—

“Maybe,” Aziza said, as they continued down the corridor to the next room, “it’s drawn to your craft. In some myths, sleep is death’s brother.”

That shouldn’t have been reassuring. But it was.

Leo kept watch after that while Tristan followed Aziza into classrooms, closets, offices. The music never got any louder or quieter; it stayed with him like a tickle in the back of his throat, something he could almost but not quite ignore. He had been right; it was his mother’s playlist. The songs were in the right order and everything. Cyndi Lauper, Time After Time. Shania Twain, You’re Still The One. It was alphabetical by artist. Who the hell put playlists in alphabetical order? Only his mother. He’d almost forgotten about that; he’d wanted to forget.

The horseshoe talisman stopped the sandman from putting new nightmares into his head, but it could still use what was already there, could pull things out of him and warp them. It wanted him disoriented and on edge.

“Don’t listen,” Leo said worriedly, catching him when he zoned out again.

“My mother can’t build a good playlist to save her life,” he complained. “I wish I could change the channel.”

“Just let us know if it gets worse. You will, right?” Leo said.

Tristan had neglected to inform them that killing the hag would kill him, too, and Leo clearly hadn’t forgotten. It had only been—four, five, however many days. Leo had softly and nonconfrontationally attempted to convince Tristan that his well-being mattered just as much as ending the hag’s year-long murder spree. Then he’d given every appearance of being devastated when Tristan disagreed. Tristan couldn’t—wouldn’t—guarantee that he would always confide in them on matters of life and death, but he had said he’d try, and Leo had smiled at him as if Tristan had promised him the world. This had left Tristan too flustered to speak. Aziza, witnessing this exchange and doomed to be an unwilling passenger on Tristan’s emotional roller coaster until they got better at controlling the bond, had closed her eyes as if wishing for the sweet escape of a medically induced coma.

“I will,” Tristan said, because Leo would take him at his word, even when all evidence suggested he shouldn’t.

It was toward the end of the last hallway when the sound of their footsteps became muffled by a thick layer of dust. Their flashlights illuminated tiny specks of it drifting lazily through the air. Where the other halls had gleamed—the door handles, the floors, the light fixtures overhead—this one was dull, as if it had been abandoned long ago.

“Is this what you meant by changing things?” Leo whispered, panning his light over the locker doors caked with grime, the wall panels fuzzy with it, as if it were a kind of mold. “Is this a dream? Because I’m pretty sure I would’ve noticed walking past this before third period today.”

“No. The way it looked by day was the dream. Dust, dirt, ash—all of those can build up as a byproduct of sandman magic,” Aziza said. “It means we’re close. We’ll go downstairs next.”

The door to the stairwell was just ahead, a few feet away. They never got there. Tristan didn’t, anyway.

In the corner, something moved.

Tristan had told Aziza and Leo that he’d tried to wake someone from the dead once, and it didn’t go well. This was true.

He hadn’t confessed that there had been a second attempt, not long after the first.

It had been twilight, and the streetlamps were flaring on around him as he wandered Blackthorn’s crooked backstreets. He hadn’t yet decided where he’d be sleeping—he had spent too many nights in a row at St. Sithney’s, and he preferred to keep moving. It was important not to fall into a pattern where people could begin to recognize him or keep tabs on him. He couldn’t be a regular anywhere. The more anonymous he was, the safer for himself and everyone around him.

Something twitched in the corner of his eye, and he froze. But it was just a pigeon, slumped next to the gutter. He’d thought it was dead.

He stood over it, looking down at its dirty, matted feathers and the unnatural bend of its neck. Its wing twitched again, pathetically, and at last was still.

With a glance around to make sure he was alone, he said, under his breath: “I can buy you a little time. I hope you’re smart enough to get yourself to someplace green.”

Nothing deserved to die in the street. Not even a pigeon.

He reached out tentatively to the small, cooling body with his stolen magic. The pigeon’s neck straightened. Its wings fluttered with renewed vigor. In a moment, it was hopping to its feet and investigating the gutter for scraps of something edible. But it quickly flew off, like he’d hoped. There was a park nearby. Maybe it would make it there. He held on to its life for as long as he could—a spark of energy, dull but warm, like a coin lodged behind his back teeth—but soon enough, his fingertips prickled as the sensation left them. If he looked at them, he knew they’d be turning blue. He withdrew his magic, then, slowly and gradually. Somewhere, the pigeon would be making a clumsy descent as it died a second death.

That was it. The best he could do. He couldn’t even say with any conviction that it was better than nothing.

Under the glare of his flashlight, the thing in the corner stopped moving, and he could see then that it was a pigeon. Lying in a heap with its wings limp and muddy. It spasmed; he couldn’t tell if it was getting up or dying, but it had the same speckles as the one he’d briefly revived. Part of him knew this was all wrong. But he moved toward it anyway, entranced. Behind him, Leo made a cut-off noise, something that might have been the beginning of Tristan’s name, but Tristan didn’t look back, because the pigeon was unfolding. Like an origami bird. It opened up, layers of feather and skin peeling away to show where it was red inside; it spilled onto the tiles and—then he couldn’t look anymore. When he turned back to Leo and Aziza, though, they were gone.

Biting back an expletive, he reached for one of the silver coins in his pocket. It was cool in his hand, grounding. He pressed it to each of his eyelids in turn. The pigeon was gone when he looked up, but Aziza and Leo hadn’t reappeared, either. In fact, a glance around told him he had wandered far from where they’d been before, even though he could have sworn he’d only taken a few steps. He had ended up in a different wing of the campus.

The music had stopped. But the silence was almost more unnerving.

With a grim sense of inevitability, he started walking in what he hoped was the direction of the stairwell. He assumed the sandman would not let him get there. But he wasn’t going to stand around waiting for its next move.

“Help,” someone whispered, behind him.

It wasn’t a voice he recognized. The face, though, was familiar. Tristan didn’t bother pointing his flashlight at him, because he was illuminated the way he had been when Tristan had seen him last—as if by moonlight in the woods, the moonlight under which Tristan had buried him. It was the man Tristan had tried to resurrect. The stump where his arm had been was not bleeding, even though the wound looked raw. He limped on his torn-up leg.

“Please,” the man said. “Try again. One more time.”

His remaining hand reached out to Tristan. Tristan stumbled back and into the nearest classroom, slamming the door before he dared close his eyes long enough to press the coin against them. The mournful voice outside went silent.

When he opened his eyes, he was in the woods, and the gateway tree filled his vision, stretching toward the open sky. It was whole and unburnt. Something moved in the crook of its branches—squirming, like a maggot, only far too large.

Later, they would compare notes and figure out that all three of them had encountered a vision of the gateway tree. For Aziza, it had been in flames, its bark flaking off and filling the smoky air with reddish-gold embers that seared as they brushed her skin. Leo had found himself waist-deep in freezing salt water that rose with terrifying speed. It had been too dark to see the gateway tree, but its roots had moved lethargically under his feet, making the water slosh around him. Something made a noise between a groan of agony and the creak of an old house, and the sound had echoed through a space that was so vast he knew he’d never reach the edge before the water closed over his head.

Only Tristan faced the gateway tree as it had been in the early days of his contract, at its weakest, because the hag hadn’t fed in years. The others saw an ending; he saw the beginning, and felt the weight of all the days to come bearing down on him.

“I was waiting for this,” Tristan said. “It’s the obvious choice, I guess.”

It wasn’t real. He knew that. But his throat closed up anyway, and his heartbeat boomed in his ears.

The hag opened her mouth and spoke in a voice that wasn’t hers—deep, reverberating, and toneless.

“The three of you should have left me alone,” she said. “Haven’t you been through enough?”

Tristan’s hand shook as he raised the coin to his eyes again. When he lowered it, the hag was gone, but the voice followed him as he fled the classroom.

“Do you think that dreams can’t hurt you?” the sandman said.

The corridor went on forever. No matter how fast he walked, he couldn’t get to the end. His chest was tight, his breaths shallow; he could feel himself wanting to break into a run, and that would do nothing but tire him out, so he forced himself to stop instead.

The nearest door drifted open, as if pushed by a breeze.

“If I cut your chest open and reach inside of you to feel the shape of your heart, is it okay because it only happened in a dream?” the sandman said, low and languid, delivering its threat as though it were a lullaby. “You cannot conceive of the torments I have witnessed. You cannot imagine them. But if you do not leave now, you will. I’ll never let you forget.”

By the time Tristan heard the footsteps, they were almost upon him. He didn’t have a chance even to move, to face whatever was coming head-on—

“That’s enough,” Leo said, brushing past him and slamming the door. He turned back to Tristan with a grimace. “God. I was starting to worry I’d have to spend the whole night looking for you. I guess it had a hard time keeping track of all three of us at once.”

“It got you, too?” Tristan asked. His hand rose to press over his frantic heartbeat, willing it to slow. Embarrassing, he thought, that he was still so easily frightened by nightmares when he had lived through far worse.

Leo nodded. “I lost you and Aziza right around the same time. We should see if she made it downstairs.”

He offered his hand. Tristan took it without hesitation. His fingers laced with Tristan’s, warm and reassuring, as he led the way back down the corridor.

It must be confusing for the sandman, Tristan thought. His free hand moved to his pocket, to hide the fact that he still held the silver coin so tightly it would likely leave an impression on his palm.

In Tristan’s mind, the only difference between the Leo that touched him like this and the one that didn’t was time. The sandman had gotten the two mixed up. Like Tristan did, sometimes.

He held on, even as the thing wearing Leo’s face guided him to the elevator. That was another error; Aziza had warned them to steer clear of the elevator and stick with the stairs. But the sandman didn’t realize that. It pressed the button. A few beats of silence, and then a chime as the doors slid open. The hand holding his gave a quick squeeze before letting go—it was painfully realistic—so that Tristan could enter first.

He did; and as he passed, he caught the sandman by the collar and used his weight to fling them both to the ground.

Aziza had said the sandman was coming for him first. That implied it would then choose someone to go after second, once it had put Tristan to sleep alongside its other victims. If Tristan had to guess, the sandman would save Aziza for last. That meant Leo, the real Leo, would be its second target. So Tristan couldn’t let it get that far.

As he and the sandman crashed to the floor, the sandman half on top of him and already twisting away, Tristan shoved closer and pressed the coin to its neck. The noise that came out of it was inhuman, a ghastly cry that sent a chill down Tristan’s spine. It writhed with pain, and it changed, until it no longer looked anything like Leo. It was humanoid, but its flesh was—like light through the inside of your eyelids, shifting colors in an expanse of black. He forced the coin into its mouth, and it choked, seizing.

This would buy him seconds, maybe. He scrambled to his feet, reaching into his bag for the container of salt—they’d each brought one—and pouring it out in a sloppy circle around the sandman as it coughed out the coin and struggled to its feet.

It breathed heavily—and that struck him as strange, that a creature made of dust and dreams required oxygen to live. If you were magic, you shouldn’t need to breathe. Its eyes were on him, he thought, but he found in its true form that it was hard to look at it directly. He blinked and focused on the salt circle instead, making sure he had not left any gaps.

“This won’t hold me,” it seethed. “I will come for you.”

Tristan nodded. “I know.”

It shouted after him as he walked away. The elevator shaft was in the middle of the building; the stairs were on the outside, at the ends of the hallways. He picked the direction he thought would lead him back to where he’d lost the others, and after jogging a few minutes he almost collided with Aziza and Leo as they stumbled out of a classroom.

That was really Aziza. He knew it instantly and didn’t know how he knew, at first, until he realized that it was the bond. He could tell when she was close by. And if that was really Aziza, then the person next to her was probably the real Leo, too.

“Tris!” he said, relieved. “You disappeared on us.”

“What happened?” Aziza glanced down at the container of salt he still clutched in the hand that wasn’t holding his flashlight.

“It’s—it’s in the elevator,” he said. “For now.”

They had to hurry. Now that the sandman had failed to scare them off, it would focus all its energy on draining its victims, taking as much as it could from them before they stopped it. An assault like that could destroy the victims’ minds; they’d lose their ability to dream, forever. Their hopes and aspirations would go with it, everything that gave their waking lives direction and meaning. It wasn’t death. But it was still a terrible fate.

The door to the stairwell clanged as they opened it. They took the stairs at a run. There was a short landing in the middle with a turn, and then two doors at the bottom: the one into the first-floor hallway and an emergency exit that led back outside.

Aziza tucked her flashlight into her pocket, reached for the door to the hall, and stopped short—as if her hand had tangled in an invisible net.

It was bizarre to experience Aziza’s intuition through the bond. He knew what her next move was even before she pivoted, her gaze falling on the shadowy place under the stairs.

There had been nothing in the darkness a moment ago, he was sure of it. Or was he? Maybe they really had walked right past them: the sleepers in their cobwebby shrouds, wrapped up as if in blankets, slumped against the wall and each other.

“The whole time . . .” Leo muttered, scanning their faces with his flashlight. They were pale and thin, but breathing. The dust in the air was so thick that Tristan’s eyes stung.

“The sandman had its magic in layers around them, hiding them in dreams that mimicked the real world,” Aziza said. “The outer layers were upstairs. I’ve been cutting through them with my craft. I couldn’t find the inner layers until we got closer, it was so seamless.”

She knelt beside the sleepers. Leo kept his flashlight on her as she placed silver coins over each of their closed eyelids. This would stop the sandman from feeding on them and release them from the sleeping spell, allowing them to wake up naturally. Tristan watched the two exits and the stairs. He had left the sandman in the elevator. If the salt circle didn’t hold it, would they hear it coming? He strained his ears, listening to the near-perfect silence.

The chime of the elevator resounded through the hollow first-floor corridors. At the same time, the upstairs door clattered open. The emergency exit a mere two feet from Tristan rattled, as if something was trying to unlock it from the outside.

Aziza shot to her feet.

“You’ve stolen from me, gatewalker,” the sandman said, and its voice came from all three directions. In the hall and on the second-floor landing, footsteps approached. “What shall I take from you in return?”

“The time for bargaining is gone,” Aziza said. “You got greedy. I hope you enjoyed the feast while it lasted. It’s time for you to go now.”

“I would not bargain with you even if you begged,” it said.

The footsteps stopped; the voice fell silent. From the shadows beside the sleepers—the one place they weren’t looking—the sandman emerged.

In the confused, crisscrossing beams of their flashlights, it appeared as a long, tall silhouette, its proportions only vaguely humanoid. It was as the music and the woods had been, unreal and yet absolute. It had hidden behind a dream of the dark, a final layer of concealment; Aziza, searching only for its victims, must not have thought to look any further once she’d found them. The sandman wrapped a hand around Aziza’s good wrist, unbalancing her, dragging her backward.

Tristan threw himself after her, knees hitting the ground with a jarring pain, his flashlight rolling away; he caught two fistfuls of her borrowed hoodie, but all that happened was that he got dragged with her and then he lost his grip. But it gave her time to shrug out of her backpack, Leo taking it from her and retrieving her silver pocketknife. He was lunging at the sandman then, and Tristan fell back, digging through the backpack the moment Leo moved. Tristan resisted the urge to watch the struggle, but he caught glimpses from the corner of his eye: Leo slashing into the shadows, Aziza wrestling her arm free, the sandman making a terrible, furious noise—a gnashing sound that hurt Tristan’s ears—but then Tristan found what he was looking for. The net bundled at the bottom of the backpack. Aziza had woven it a long time ago, silk thread soaked in peppermint oil and imbued with Aziza’s magic. It was flimsy and worn-out, and the gaps were wide enough in some places to stick his head through. But when he shouted for the others to get out of the way and then flung it over the sandman, the net did what it was made for. The sandman fell to its knees, struggling against the net as if it hurt. Tristan still couldn’t quite look at the sandman directly, not for long—his gaze slid right off it—but the places where Leo had stabbed it trailed wisps of a smokelike substance that dissolved into the air. Its eyes, when it looked wrathfully up at them, had wide white pupils like distant lights.

The three of them stood together, catching their breath. Leo inspected the knife, brow furrowed—it was spotless. The sleeping victims began to stir; one of them shifted, and the silver coins fell off her eyes, striking the ground with a clatter.

“Anyone hurt?” Aziza said, and when they shook their heads: “Okay. Let’s get him secured.”

They tied off the net as the sandman promised vengeance and eternal nightmares.

“Hush,” Aziza said, not angrily. “You came into human territory. You took more than you needed. You know you did wrong; your own folk will tell you that.”

They would have to call an ambulance for the sleepers. Be gone before the ambulance got there. Get the sandman back to the car, and transport him to the boundary.

Tristan watched the sandman claw ineffectually at the net. For an instant, when he caught the sandman’s eye, the hag’s scarred face flashed before him.

Nightmares could still hurt him, but he would outlive them. He understood that now. He had wanted to prove something, earlier, he remembered vaguely, but he couldn’t wrap his mind around what that was anymore. Something about his strength or lack thereof. Maybe it didn’t matter. Strength didn’t need to be a quality he always had, a permanent part of him, the way it was for Aziza and Leo. If his brand of strength never amounted to more than the split-second decision that let him keep outliving the nightmares for another moment, for another day, then—that was fine with him.

“You two go ahead,” Tristan said. Because it felt like something useful he could do, and he was learning that he liked being useful. If he did it often enough, maybe it would make up for all the times when he would inevitably fall short. “I’ll give you a ten-minute head start before I call.”

Aziza and Leo glanced at each other and then back at him, perfectly in sync.

“Nope,” Leo said. “Bad plan. Not happening.”

“What? Why not?”

“There’s no need,” Aziza said. “They’ll be fine. We’ll send someone for them once we’re clear.”

“I’m faster with the hounds anyway. I’ll be waiting for you at the boundary by the time you get there.”

“So you can sit here in the dark and mope?” Aziza said. “No.”

“It’s not moping, it’s brooding. Much more dignified,” Leo told her, with a conspiratorial grin at Tristan. “But still no.”

It dawned on him that this was not a battle he’d be winning. And that was fine, too.